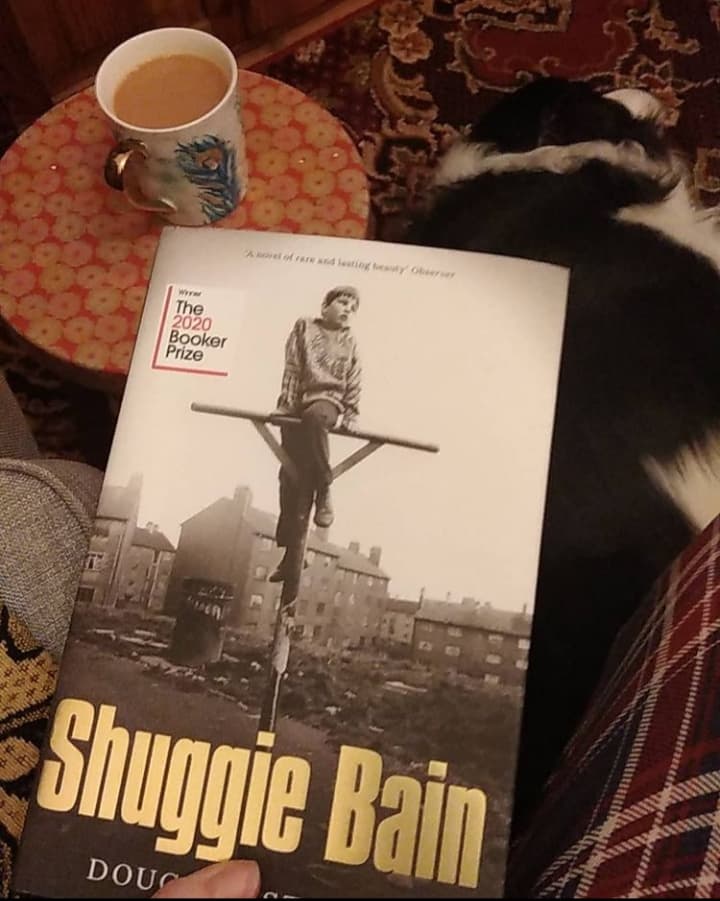

After reading Shuggie Bain, ‘Young Mungo’ felt like we were returning to the same housing estate and doing a tour around the flats to get cosy with the neighbours. We still have the alcoholic single mother and the three neglected siblings, Mungo being the youngest.

In saying that, after reading Shuggie Bain, I did instantly crave a follow-up with a teenage Shuggie. I’m not saying Mungo and Shuggie are one in the same character but it really feels that way.

‘Young Mungo’ also felt less linear than Shuggie Bain, and initially the time-hopping was a little disorientating and I questioned its purpose. We are taken back and forth between the ‘now’ and a camping trip Mungo is forced into with two creepy guys from AA, but it does all tie up in the end.

These are very teeny tiny squidgy little question marks that are buffered out of the way by the beautiful writing, the sense of place, the big fully rounded heart-breaking characters. This did not disappoint, though it is hard not to compare the two novels. On that note I would say that if you enjoyed ‘Shuggie Bain’ then chances are you will also enjoy Young Mungo, but it’s worth being cautious of the fact that ‘Young Mungo’ definitely treads a darker path; it is rife with violence and sexual assault.

There is still a humour to how people go on, their sayings and curses and philosophies on life. I found it interesting that Mungo’s violent brother Hamish is known as HaHa, and his dutiful oppressed sister has a nervous laughter that erupts even in tragedy.

Looking back, there was imagery of water and being submerged and things surfacing that we try to hide – for instance Mungo has a tick that makes his face twitch, so his emotions can be read no matter how hard he tries to mask them, his brother has to act tough, a leader, aggressive, but when he breaks out of that role, there is a softness hidden below.

‘None of the men could tell ye how they really felt, because if they did, they would weep, and this fuckin’ city is damp enough.‘

Mungo grapples with the weighty pressure of ‘being a man’ and what that means, the confusion around his emerging sexuality, whether he is readable to others, the danger that put him in, and then his blossoming relationship with a Catholic boy, James.

James Jamieson is like a glittering gem of innocence amidst the injustice and concrete. I enjoyed their relationship so so much, especially how Mungo becomes more comical and expressive in James’ company, no longer just defined by his role within his family. We see his true self emerge, and he has strength and empathy in equal measure. I could happily read a book just about these two, where they run off to the wilderness to forge a life together, playfight in the long grass, eat chips by the sea.

This novel definitely picks up speed from about half way, like you’ve climbed a hill and are rolling down towards a load of broken glass. You basically know (or presume) going in, that there can be no happiness in this world, only the fleeting sort like Mungo’s mum feels after a drink. But you can’t stop tumbling towards it all.

What really shone through for me was the way people (tried to) look after one another, the little gestures, the unconditional love. Nothing could ever stomp that down completely.